Research on diagrammatic guide signs was part of my first job after college at a consulting firm named Serendipity, Inc. My first task was the same for every project: we called it “getting smart”. It consisted of two steps: (1) Read everything we had that might relate to the project objective; and, (2) write down any thoughts that came while we were reading. The company had learned that those first thoughts almost always contained elements of a solution. We came out of this first task with lists of questions and ideas.

Serendipity, Inc.

Our objectives were simple:

- Find which diagrammatic sign designs worked best on Interstate highways

- Determine if they would work and where they would work best. Earlier studies showed that most accidents (and most fatal accidents) were in the vicinity of interchanges, with the highest concentrations near major interchanges. So we focused on this.

Our task was to find a way to test guide signs indoors. Our approach was:

- Tell the test subject(s) their destination

- Project a picture of a road, so they could see how many lanes there were

- Project a sign on a screen for a short time, typically a second – based on the thought that drivers were busy near interchanges

- Ask the test subject(s) to say what lane they should be in – based on the assumption that last second maneuvers could cause accidents and that early lane positioning was desirable

We moved from asking (for a single subject) to some buttons to be pushed that we recorded, so we could test a group of subjects. This worked, so we received permission from the Smithsonian Institution to use their facilities and access their visitors as test subjects.

Federal Highway Administration

After the project was completed I left Serendipity. After I worked for a few months at another human factors firm, I was hired by the Federal Highway Administration – who was taking over the project and wanted someone who was involved in the earlier work. I was the only junior person, so I was hired.

FHA’s job was to coordinate more comprehensive testing. Their first step was to validate the results. To do so they set up two instrumented cars. These had a small projection screen mounted next to the rear view mirror and a slide projector in the back seat. The testing was similar to the laboratory work:

- Tell the test subject their destination

- Project a picture of a sign at the appropriate time

- Take notes on the car’s movement and the driver’s heart rate

There were three groups of test subjects:

- Ordinary people, 25-60

- Retired ministers

- Airline pilots

Everything went well, and there was only one incident: One of the instrumented cars was loaned to us by Ford; they had instrumented it and used a gold-plated steering wheel to collect heart rate and – for public relations purposes – had used a convertible. That car was following a truck when a chain broke and the truck’s load – pressurized acetylene tanks for welding – began to fall off the back, just in front of the instrumented car. The driver – fortunately an airline pilot – weaved among them and dodged any that would have landed on the car. His heart rate didn’t change while this was going on – only afterwards!

FHWA Testing On The Road

The instrumented car tests indicated that diagrammatic signs had real potential, so we began the final tests: We – the four people at FHA on this project – would set up two test signs and develop methods of data collection and analysis. Simultaneously, an RFP (request for proposal) was sent out to select a firm for a more comprehensive test on the I495 Beltway around Washington, DC.

The two test signs were an issue: we couldn’t find a company that would install them on our schedule as all local companies were booked for months. So we decided to install them ourselves. First, we needed a “before” study. The only approach we could follow on short notice was super-8 video cameras, run at one frame per second. We planned to use four, so we bought six. These were set up on tripods to show the traffic upstream and downstream from each sign. My job was to place the cameras and their operators, and to check back hourly and provide food, drink, and relief. After a few days the first camera broke; I’d already found a local firm to repair it so I took it there and asked them what had happened. They told me that the camera wasn’t really designed to run for long periods at one frame per second; that each camera should be rebuilt every 100 hours to be reliable. Well, that’s why we were doing this; to find out what would happen. I looked at industrial grade cameras, these were much more expensive and couldn’t be rebuilt locally. So we stayed with the consumer grade and planned to buy more.

After finishing the “before” data collection we spent a week installing the new signs ourselves. We rented and put up scaffolding. The new signs were delivered to the sites, stacks of 4×8 plywood, each marked for where it should be installed. We replaced the old signs with the new signs. I’d never worked on scaffolding before, and didn’t like heights. But I got used to it. It took a full week in the hot sun, but we got it done. And we spent another two weeks collecting “after” data.

During the data collection I felt like everything that happened on the few miles where we were working was my responsibility. I drove up and down it dozens of times a day – frequently stopping to deliver food, drink, film, cameras, and people. Any time a car stopped on either side of the highway, I stopped to help. By that time I knew every store and repair stop within miles. Once, it was a truck with two appaloosa in a trailer – beautiful horses. After I helped them they gave me their card and asked me to visit sometime. I’m still sorry I didn’t.

Contractor Testing

This was in the fall; the contract was expected to start early in the next year. They would collect “before” data, change about a dozen signs, and collect “after” data. The sign change was scheduled for the summer months to include as many tourists as possible. The winning company also did something that we couldn’t: they planned to use tape-switches on the highway to measure traffic by lane. They also planned to put some of them on the lines near the interchange that cars were not supposed to cross. All of these were to be connected with wires so that the data could be recorded. While this was much superior to our camera approach, they also planned to operate cameras – primarily for backup. Everything went as they planned and they submitted their final report on schedule.

Results

There were also studies done by eight states; in total, there were about twenty studies of diagrammatic guide signs. From these, there were three major findings1:

- More time is required to read, understand and react to diagrammatic signs in comparison with conventional signs with the same number of legends…

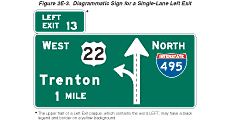

- Drivers have certain expectancies as they drive along a highway. Because exits are usually to the right … A left exit violates the expectancy of both exiting and through traffic. It is at such exits where unusual maneuvers are required that diagrammatic signs benefit driver

- Benefits from diagrammatic signing … In other words, because drivers decide earlier on the appropriate path to reach their destination and position themselves accordingly, there is less indecision at the gore proper [where the roads split].

Several years after the final report, there was a study of accidents and fatalities at the changed interchanges. These found a 20% reduction in both at the recommended locations for diagrammatic signs: left exits from Interstate highways. Overall, this was an unusual research project because it encompassed multiple sign testing methods ranging from the laboratory, through instrumented cars, on-highway, and before/after accident and fatality records. While my part was small, it provided a standard that I have remembered.

April 3, 2020

1 Pages 4-6, Diagrammatic Guide Signs For Use On Controlled Access Highways, Report No. FHWA-RD-73-21, December, 1972.

Leave a Reply