Twenty-five years ago, after I learned that the stock market had become inefficient, I began to think about investing in an inefficient market.

Together with a friend who was also an ex-student, I attempted to start an investment management firm. This didn’t work for a variety of reasons, but I used the same analysis I discussed in my Why The Stock Market Is Inefficient and Why Market Efficiency Is Important posts to model an investment strategy. That is the strategy I will present below. How well did it work? It beat the market by more than 4% per year over all periods tested. However, such a test has potential biases and the market may be very different today – so beware! I am not responsible for the results of using the analysis I describe below!

Caveat: I don’t do investment management – not even for my own funds; someone else does it for me. I do this because it seems best for me; the same “transient enthusiasms” that will populate this blog distract me from managing my investments. Since I doubt that I can manage them well, I don’t do it.

Steps To An Investment Decision

Step 1: Find potentially under-priced companies – low P/E companies are a good start.

Step 2: Use the Fruhan model to find which low P/E companies are actually under-priced.

Step 3: Evaluate the under-priced companies – apply conventional financial, strategic, and market analysis to determine if the under-priced companies are well-run, effective companies. That is, if you consider them “good”.

Step 4: Watch the “good” under-priced companies for better-than-market momentum – you are looking for companies whose price is increasing faster than the market. This isn’t simple momentum, which expects the beat-the-market performance to continue because it exists. Your price momentum is biased in your favor by your earlier steps: The logic is: because the company is under-priced, the company is more likely to continue to beat the market until it is over-priced.

Deciding When To Sell

Watch the price momentum:

- If the price momentum falls below the market

- If the company is fully or over-priced, then you should sell the stock

- If the company is under-priced, then perhaps you should sell the stock and buy another Step 4 company

The “perhaps” statement above is the problem. For me, logic doesn’t help with the decision; my preference is to test the strategies with some market data – but I no longer have this. So, basically, my advice here is to “wing it”.

The Fruhan Model

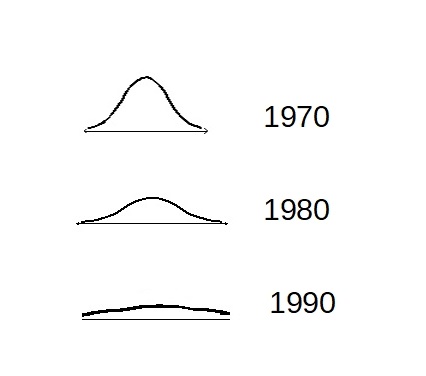

The chart below is found on pages 12-13 of William Fruhan’s Financial Strategy book1.

Here are the steps to use the model:

- Estimate the percentage point spread of extraordinary returns (-5, 0, +5, +10, +20)– these are in percent; compare the return on equity to that expected by the market.

- Estimate the number of years that extraordinary returns are expected (5, 10, 15, 30)– to address this you need to know why and how those returns were achieved.

- Estimate how much of the earnings can be reinvested in the extraordinary returns (0.3, 0.5, 0.7, 1.0, 2.0)– again, this requires that you know how the returns were achieved.

- Find the value in the chart; it is the multiple of the company’s book value that the extraordinary returns have justified.

Note: When I do the above four steps I use the adjustments I recommend in my Book Value And The Cost Of Capital post and I recalculate the return on equity with those adjustments.

I highly recommend that you obtain and read Fruhan’s Financial Strategy book because it has insights beyond the model and the mathematics that generated the model.

This approach could also be used with over-priced companies by selling short. However, this is more risky as you could lose your entire investment if the stock price increases enough. Additionally, there is usually a carrying cost for short sales plus you must pay any dividends that the company issues. These combine to limit the potential returns of short selling. Thus, the risk-adjusted returns are less.

Relating Investment Strategy To Market Efficiency

Buying under-priced (and selling over-priced) stocks aids market efficiency – it’s effect is weighted by the amount invested. However, the data that I analyzed twenty-five years ago showed that some mis-priced stocks remained mis-priced for decades. This is the reason that we added the momentum requirement before purchase. A single small investor can expect to have no effect on market efficiency. My hope is that this and my other stock market posts generate a broader interest.

If this approach should become more widespread the returns will occur more quickly. As the market returns to efficiency then the returns will disappear – as the Efficient Market Hypothesis says they should. However, it took more than a decade for the market to become inefficient – so it should also take more than a decade for it to return to efficiency – and it may never do so.

March 22, 2020

Footnotes

1 Fruhan, William E. Jr. (1979). Financial Strategy: Studies in the Creation, Transfer and Destruction of Shareholder Value. Homewood, Illinois: R. D. Irwin. OCLC878176877.