The stock market is inefficient because the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH) is believed. While this sounds peculiar, the EMH may be unique in becoming false because it is believed.

Virtually anything that you read says that we have an efficient market – but what does that mean? Here’s a definition, the Business Dictionary says: “Market where all pertinent information is available to all participants at the same time, and where prices respond immediately to available information. Stock markets are considered the best examples of efficient markets.”

That sounds good; but what makes it happen? Here’s the explanation I was taught: If a stock price falls below its “proper” value then investors will purchase that stock and drive its price up until it is properly priced; the converse is true for overvalued stocks. Therefore, stocks are “properly” (efficiently) priced.

So, the stock market is efficient because investors are looking for mis-priced stocks – that seems reasonable. What do you think would happen if we taught everybody that the market is efficient for fifty years? Do you think investors would still be looking for mis-priced stocks after being told for so long that there are none? I don’t – and the problem is, we have done exactly that.

So, why does everybody believe the market is efficient?

The Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH)

The logic behind the EMH was first proposed around 1900. It became popular in the 1960s due to Paul Samuelson and Eugene Fama; it became mainstream in the late 1960s by inclusion in the Finance textbooks of the time. Here’s a formal definition from Wikipedia:

The efficient-market hypothesis (EMH) is a hypothesis in financial economics that states that asset prices reflect all available information. A direct implication is that it is impossible to “beat the market” consistently on a risk-adjusted basis since market prices should only react to new information. Since risk adjustment is central to the EMH, and yet the EMH does not specify a model of risk, the EMH is untestable.1 As a result, research in financial economics since at least the 1990s has focused on market anomalies, that is, deviations from specific models of risk.2

The EMH is why everybody believes the market is efficient. Note the “H” for “hypothesis”, that’s a formal simile for “I think”. It might be true – but it’s called “untestable” – so it’s just an idea.

So what does it take for the EMH to be true? The minimum is a large number of investors (or computers) looking for mis-priced stocks. But if the EMH is true, why would they waste their time looking for what never will be found? The only answer I’ve been able to think of is that they don’t believe the EMH – so the EMH implicitly requires that it be disbelieved. I therefore conclude:

If everybody believes the EMH then it will be false.

Testing Market Efficiency

Fama asserted in 1970 that the EMH cannot be tested because the EMH doesn’t provide a method for estimating risk. Regardless, I just can’t believe that so fundamental an idea cannot be tested.

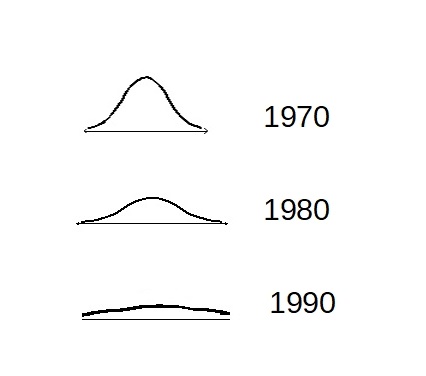

In the 1990s I thought of an approach: Divide each stock’s market value by a discounted cash flow estimate of its value3; I termed this Market/Model. As I then had access to Compustat data, I calculated this annually for each stock in the NYSE from the late 1960s to the early 1990s. Then, I plotted the frequency of these values for each year and compared the shape of the curves. In 1970 I found a strong central tendency, looking like a normal distribution:

by 1980 it had flattened:

until, by 1990, the curve appeared almost flat.

In an unpublished paper, I interpreted these results to indicate that the EMH has become false – for the reasons discussed above – and that the stock market is no longer efficient. I still believe both the results and the interpretation.

So, why did I reach that conclusion?

- Virtually all financial theories about companies consider the (Model) value of a company to be that of its future cash flows – and I calculated a version of that.

- The Market value of a company ought to be similar to the Model value.

- If they were identical, there would be a single line at 1.

- Since they are only similar, they should be around 1, so that the plot should show most of the Market/Model values near 1.

- Therefore, if the market is efficient the Market/Model should show a strong central tendency – translation: It should show a hump in the middle. It doesn’t, so the market is not efficient.

Forces Against Market Efficiency

There have been no forces (or voices) for market efficiency since the EMH was first proposed – simple belief in the EMH has accomplished the opposite.

- Education

- Since the late 1960s college business majors and MBAs have been taught the EMH – and have accepted it as true.

- The Internet is a major source of impromptu education – and teaches the EMH as true.

- Institutions – mutual funds and retirement funds

- Stocks held by institutions grew steadily from 5% of the stock market after World War II to 80% today.

- Institutions choose highly-trained people to manage their portfolios; these people generally believe the EMH and don’t waste their time looking for undervalued stocks.

- Passive investment management – Index funds began in 1976 and now have more assets than active institutional management – these cannot look for mis-priced stocks.

- As index funds own the same stocks in the same proportions as the index, they are technically neutral in their effect on market efficiency. However, I consider them a force against because they prevent their investments from being a force for market efficiency.

- This leaves 20% of the market for individual investors – and they likely know of the EMH.

Only 60% of the market could support efficiency (half the institutions plus individuals) and the market forces against efficiency have grown steadily since the EMH was proposed. So I believe that market efficiency has declined throughout this period. However, as I no longer have access to Compustat I can’t test it. (To anyone who does have access: I will happily cooperate in repeating and extending my analysis.)

Miscellaneous thoughts

There might be subsets of the markets that are efficient because the stocks in these subsets are more closely watched by investors and analysts.

Why is market efficiency important? See my Why Market Efficiency Is Important post.

April 5, 2020

Footnotes

1 Fama, Eugene (1970). “Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work”. Journal of Finance. 25 (2): 383. JSTOR 2325486

2 Schwert, G. William (2003). “Anomalies and market efficiency”. Handbook of the Economics of Finance. doi:10.1016/S1574-0103(03)01024-0.

3 Fruhan, William E. Jr. (1979). Financial Strategy: Studies in the Creation, Transfer and Destruction of Shareholder Value. Homewood, Illinois: R. D. Irwin. OCLC878176877.

Leave a Reply